What is a storm surge?

12 November 2010

Last month, as Severe Typhoon Megi approached Hong Kong, there was fear about the storm surge it might bring.

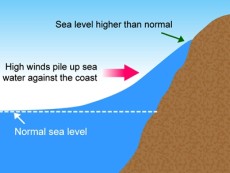

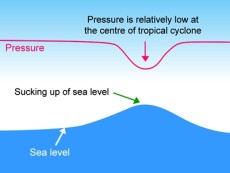

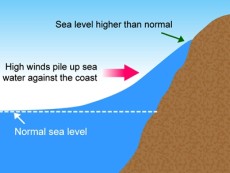

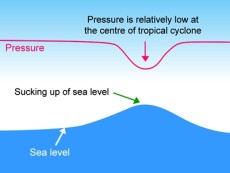

Simply put, a storm surge is a raised sea brought by tropical cyclones. The winds of a tropical cyclone (Figure 1) are the main culprit in water level rise, while its low pressure (Figure 2) contributes to a lesser extent.

Figure 1Rise of sea water due to the storm's strong winds

Figure 2Rise of sea water due to the storm's low pressure

Over the past hundred years or so, there have been two big killers, one in 1906 and the other in 1937, causing a heavy toll of 15,000 and 11,000 respectively.

The height of water brought by a storm surge depends on the water depth (i.e. bathymetry) and the shape of the coastline. It could be made worse if the arrival of the surge comes with the astronomical high tide.

The geography of Hong Kong suggests that it is vulnerable to storm surges when winds come from the east or south. This could be visualized if we bear in mind that a tropical cyclone's winds blow in a counter-clockwise direction.

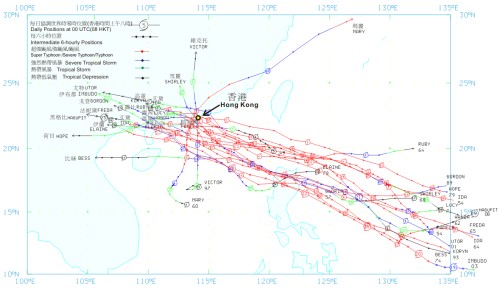

Have a look at Figure 3, which shows the tracks of the past 20 tropical cyclones that brought the most significant storm surges to Hong Kong, based on available data. The record holder was Typhoon Hope in 1979, which raised the water by 3.2 metres at Tai Po Kau in eastern New Territories. Overall, the tracks indicated that either the storms hit Hong Kong directly or almost, or they swept past Hong Kong from the west or south.

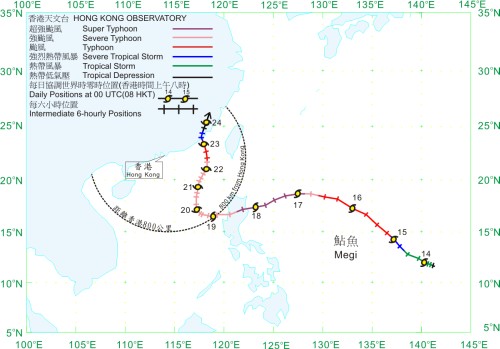

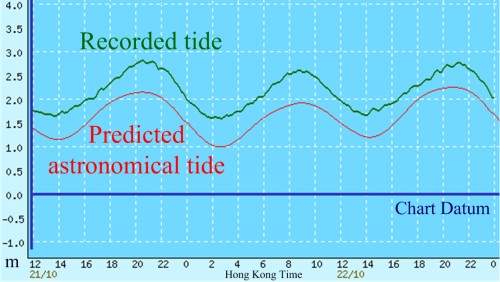

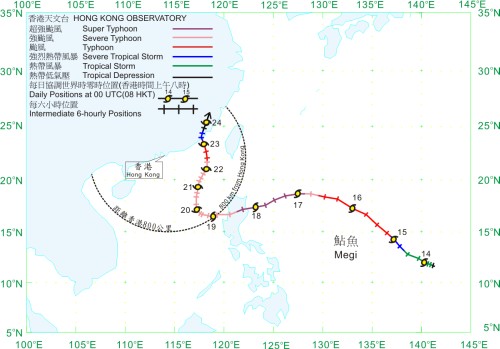

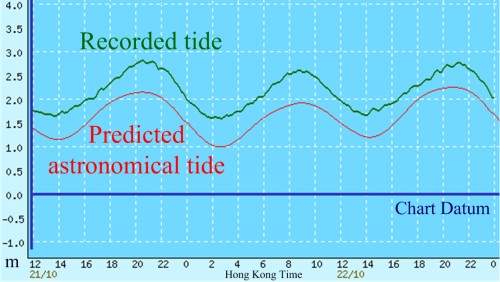

In comparison, Megi's track (Figure 4) was quite different. As it maintained a distance of 400 kilometres from Hong Kong during its passage, the water rose only 0.7 metre locally (Figure 5), of which 0.5 metre was associated with the northeast monsoon prevailing at the time. Thus Megi's storm surge was just 0.2 metre.

Figure 4Track of Severe Typhoon Megi

Figure 5Sea level at Quarry Bay from noon on Oct 21 (Thu) to midnight on Oct 22 (Fri)

As a matter of fact, the northeast monsoon had caused minor flooding in the past. The low-lying areas at Sheung Wan in western Hong Kong were once vulnerable spots when in winter time, the strong northeast monsoon combined with a high tide pushed the water up. The problem has largely disappeared after improvement in the infrastructure.

Because of the havoc wreaked by storm surges, the Observatory made calculations and projections in the 1970s to mitigate the possible damage to new town developments. For this reason, places like Shatin in northeast New Territories had been reclaimed an additional 3 metres.

In weather forecasting, the Observatory runs a storm surge model every time a tropical cyclone approaches the south China coast and alerts the public to the danger of storm surge if any.

B.Y. Lee and W.C. Woo

References:

1. Wong C F and Li K W, Sea level anomalies in Hong Kong due to strong monsoon, The 21st Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Seminar on Meteorological Science and Technology, Hong Kong, China, 24-26 January 2007 (in Chinese)

2. Wong W T and Wong C F, Storm Surge Forecast in Hong Kong, Technical Seminar on Marine Hazards Forecasting, Beijing, China, 4-5 December 2008 (in Chinese)

Simply put, a storm surge is a raised sea brought by tropical cyclones. The winds of a tropical cyclone (Figure 1) are the main culprit in water level rise, while its low pressure (Figure 2) contributes to a lesser extent.

Figure 1Rise of sea water due to the storm's strong winds

Figure 2Rise of sea water due to the storm's low pressure

Over the past hundred years or so, there have been two big killers, one in 1906 and the other in 1937, causing a heavy toll of 15,000 and 11,000 respectively.

The height of water brought by a storm surge depends on the water depth (i.e. bathymetry) and the shape of the coastline. It could be made worse if the arrival of the surge comes with the astronomical high tide.

The geography of Hong Kong suggests that it is vulnerable to storm surges when winds come from the east or south. This could be visualized if we bear in mind that a tropical cyclone's winds blow in a counter-clockwise direction.

Have a look at Figure 3, which shows the tracks of the past 20 tropical cyclones that brought the most significant storm surges to Hong Kong, based on available data. The record holder was Typhoon Hope in 1979, which raised the water by 3.2 metres at Tai Po Kau in eastern New Territories. Overall, the tracks indicated that either the storms hit Hong Kong directly or almost, or they swept past Hong Kong from the west or south.

In comparison, Megi's track (Figure 4) was quite different. As it maintained a distance of 400 kilometres from Hong Kong during its passage, the water rose only 0.7 metre locally (Figure 5), of which 0.5 metre was associated with the northeast monsoon prevailing at the time. Thus Megi's storm surge was just 0.2 metre.

Figure 4Track of Severe Typhoon Megi

Figure 5Sea level at Quarry Bay from noon on Oct 21 (Thu) to midnight on Oct 22 (Fri)

As a matter of fact, the northeast monsoon had caused minor flooding in the past. The low-lying areas at Sheung Wan in western Hong Kong were once vulnerable spots when in winter time, the strong northeast monsoon combined with a high tide pushed the water up. The problem has largely disappeared after improvement in the infrastructure.

Because of the havoc wreaked by storm surges, the Observatory made calculations and projections in the 1970s to mitigate the possible damage to new town developments. For this reason, places like Shatin in northeast New Territories had been reclaimed an additional 3 metres.

In weather forecasting, the Observatory runs a storm surge model every time a tropical cyclone approaches the south China coast and alerts the public to the danger of storm surge if any.

B.Y. Lee and W.C. Woo

References:

1. Wong C F and Li K W, Sea level anomalies in Hong Kong due to strong monsoon, The 21st Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macau Seminar on Meteorological Science and Technology, Hong Kong, China, 24-26 January 2007 (in Chinese)

2. Wong W T and Wong C F, Storm Surge Forecast in Hong Kong, Technical Seminar on Marine Hazards Forecasting, Beijing, China, 4-5 December 2008 (in Chinese)