Anticipated Return of El Niño*

20 June 2014

Four years after the previous El Niño event, significant warming signs re-emerged over the central and eastern equatorial Pacific in the past couple of months. The sea surface temperature in May 2014 has already exceeded the normal range over those regions, suggesting that another El Niño is brewing (by definition, an El Niño occurrence is confirmed on the basis of anomalously warm central and eastern equatorial Pacific persisting for five to six months). As the warming trend is expected to continue in the next few months as predicted by many climate models around the world, it is therefore likely that an El Niño event will become established later this year.

Incredibly, an anomaly in the ocean so far away can alter the atmospheric circulation worldwide through what is known as "teleconnection" mechanism. This in turn will affect the weather and seasonal climate in many parts of the world, including Hong Kong to a certain extent.

Will El Niño bring more rainfall?

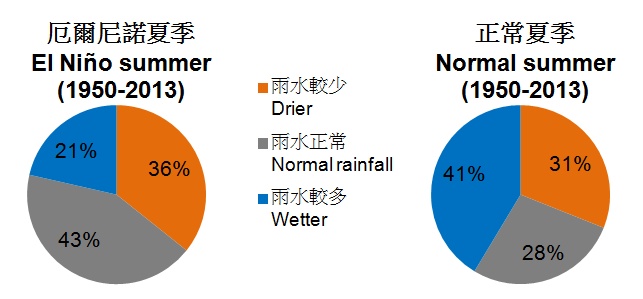

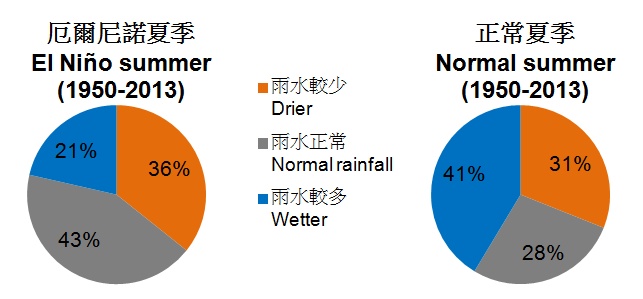

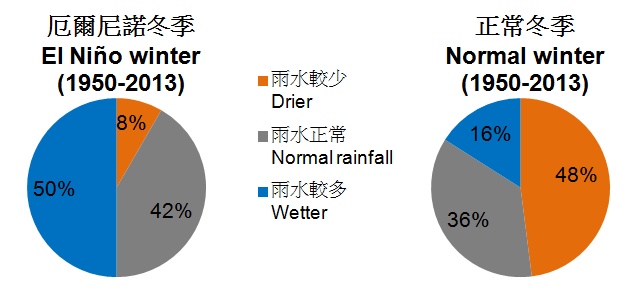

People tend to associate El Niño with heavy summer (June-August) rainfall because a strong El Niño in 1997 coincided with the wettest summer (2358.6 mm) and the wettest year (3343.0 mm) on record in Hong Kong. However, the summer of 1983, another intense El Niño year, had below-normal seasonal rainfall of just over 900 mm. Looking at the data over a long period of time, the general relationship between El Niño and Hong Kong's summer rainfall remains inconclusive. An analysis of El Niño summer rainfall records during 1950-2013 shows that the percentage occurrence of a drier summer is even higher than that of a wetter summer (Figure 1), although the difference may not be considered statistically significant taking into account the limited records available.

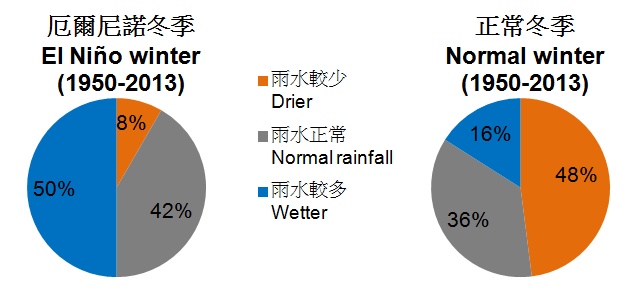

On the other hand, El Niño's impact on winter (December-February) and spring (March-May) rainfall is more pronounced. Figure 2 shows the distribution of Hong Kong's winter rainfall under El Niño and normal conditions (i.e. neither El Niño nor La Niña, the opposite phase of El Niño) during 1950-2013. It can be seen that the odds of a wetter (drier) El Niño winter will noticeably increase (decrease) compared to a normal winter.

Will El Niño affect tropical cyclones?

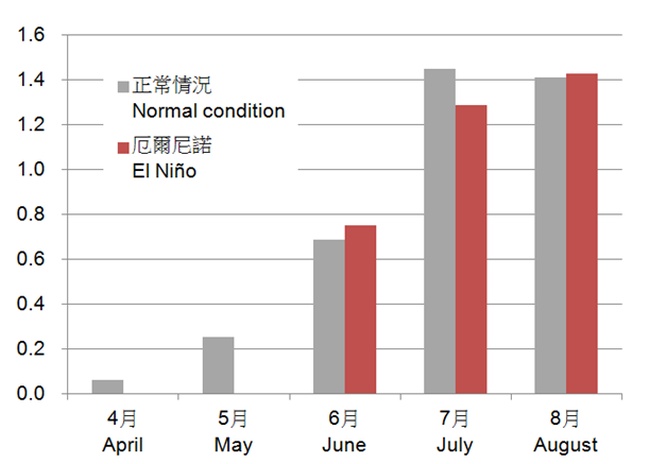

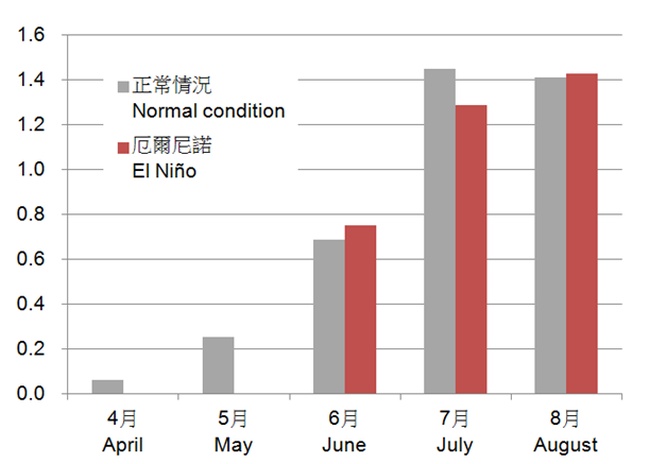

Since 1961, there has not been one single tropical cyclone coming within 500 km of Hong Kong in April and May when El Niño is in place (see Figure 3), whereas in a La Niña or normal year, the tropical cyclone season in Hong Kong can begin as early as April, e.g. 1978. That is because tropical cyclones in El Niño years tend to form further east near the central North Pacific and hence are less likely to journey as far as the South China Sea in the early season. As the season progresses, other factors come into play and El Niño's impact on tropical cyclone behaviour then becomes less well-defined.

For more information on El Niño and La Niña, please visit the Observatory webpage: www.weather.gov.hk/lrf/enso/enso-front.htm.

S M Lee

* The warming of surface waters over the central and eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean usually peaks around Christmas, hence the name "El Niño" (Spanish for "the little boy" or "the Christ Child") coined for the phenomenon.

Figure 1Distribution of Hong Kong's summer rainfall under El Niño and normal conditions during 1950-2013.

Normal condition refers to the situation of neither El Niño nor La Niña in place

during the whole season.

Figure 2Distribution of Hong Kong's winter rainfall under El Niño and normal conditions during 1950-2013.

Normal condition refers to the situation of neither El Niño nor La Niña in place

during the whole season.

Figure 3Average monthly number of tropical cyclones coming within 500 km of Hong Kong

under El Niño and normal conditions during 1961-2013. Normal condition refers

to the situation of neither El Niño nor La Niña in place during the month.

Incredibly, an anomaly in the ocean so far away can alter the atmospheric circulation worldwide through what is known as "teleconnection" mechanism. This in turn will affect the weather and seasonal climate in many parts of the world, including Hong Kong to a certain extent.

Will El Niño bring more rainfall?

People tend to associate El Niño with heavy summer (June-August) rainfall because a strong El Niño in 1997 coincided with the wettest summer (2358.6 mm) and the wettest year (3343.0 mm) on record in Hong Kong. However, the summer of 1983, another intense El Niño year, had below-normal seasonal rainfall of just over 900 mm. Looking at the data over a long period of time, the general relationship between El Niño and Hong Kong's summer rainfall remains inconclusive. An analysis of El Niño summer rainfall records during 1950-2013 shows that the percentage occurrence of a drier summer is even higher than that of a wetter summer (Figure 1), although the difference may not be considered statistically significant taking into account the limited records available.

On the other hand, El Niño's impact on winter (December-February) and spring (March-May) rainfall is more pronounced. Figure 2 shows the distribution of Hong Kong's winter rainfall under El Niño and normal conditions (i.e. neither El Niño nor La Niña, the opposite phase of El Niño) during 1950-2013. It can be seen that the odds of a wetter (drier) El Niño winter will noticeably increase (decrease) compared to a normal winter.

Will El Niño affect tropical cyclones?

Since 1961, there has not been one single tropical cyclone coming within 500 km of Hong Kong in April and May when El Niño is in place (see Figure 3), whereas in a La Niña or normal year, the tropical cyclone season in Hong Kong can begin as early as April, e.g. 1978. That is because tropical cyclones in El Niño years tend to form further east near the central North Pacific and hence are less likely to journey as far as the South China Sea in the early season. As the season progresses, other factors come into play and El Niño's impact on tropical cyclone behaviour then becomes less well-defined.

For more information on El Niño and La Niña, please visit the Observatory webpage: www.weather.gov.hk/lrf/enso/enso-front.htm.

S M Lee

* The warming of surface waters over the central and eastern equatorial Pacific Ocean usually peaks around Christmas, hence the name "El Niño" (Spanish for "the little boy" or "the Christ Child") coined for the phenomenon.

Figure 1Distribution of Hong Kong's summer rainfall under El Niño and normal conditions during 1950-2013.

Normal condition refers to the situation of neither El Niño nor La Niña in place

during the whole season.

Figure 2Distribution of Hong Kong's winter rainfall under El Niño and normal conditions during 1950-2013.

Normal condition refers to the situation of neither El Niño nor La Niña in place

during the whole season.

Figure 3Average monthly number of tropical cyclones coming within 500 km of Hong Kong

under El Niño and normal conditions during 1961-2013. Normal condition refers

to the situation of neither El Niño nor La Niña in place during the month.